The Cues Copy

Trauma cues develop through the process of classical conditioning.

In classical conditioning, there is first a natural, unconditioned response to an unconditioned stimulus.

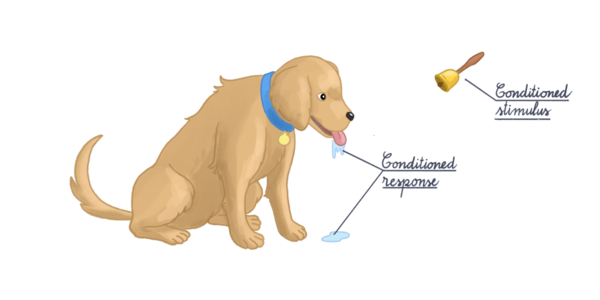

Let’s examine the famous example of Pavlov’s dog. At the start, in addition to the dog, there is an unconditioned stimulus, the food, and an unconditioned response, salivating. The association between the food and the dog’s salivation is natural and expected.

In classical conditioning, the unconditioned stimulus is paired with a neutral stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiment, food was paired with a ringing bell.

Once the dog has forged an association between the bell and the food, the bell is no longer a neutral stimulus but has become the conditioned stimulus that leads to the dog salivating.

Cues and Trauma

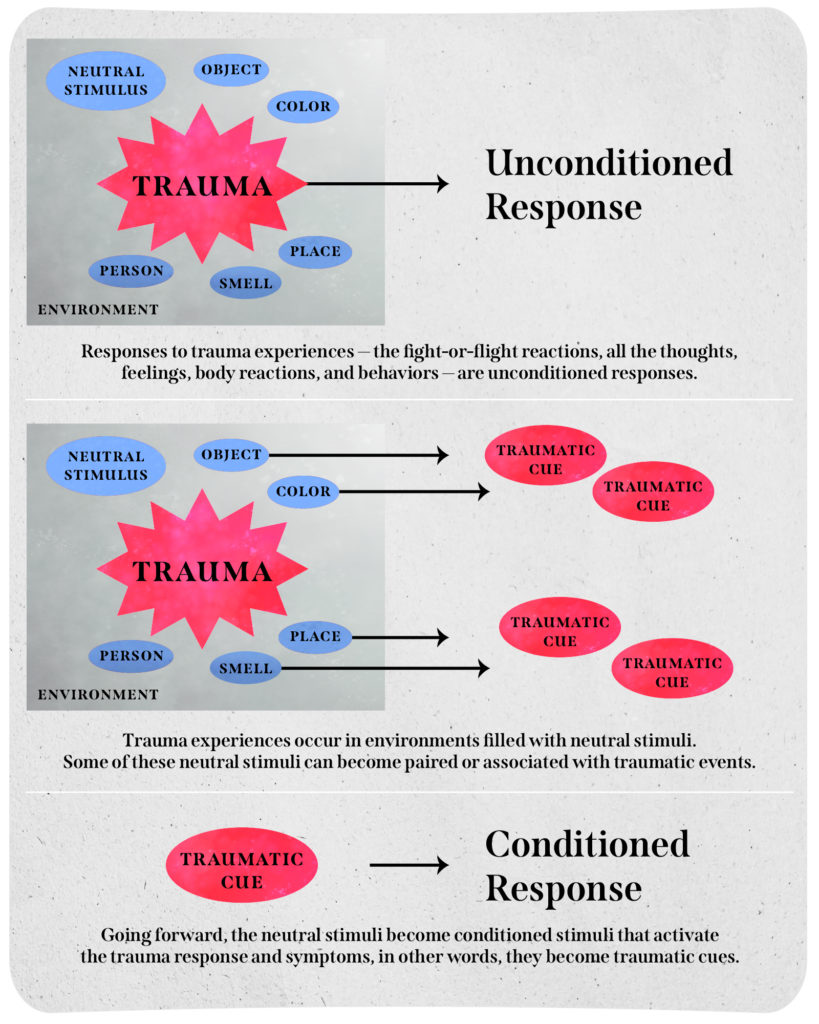

Let’s apply this principle to a trauma experience. The trauma responses, the fight-or-flight reactions—all the thoughts, emotions, body reactions, and behaviors—are unconditioned responses.

The trauma experience occurs in the context of a larger environment filled with neutral stimuli. Those neutral stimuli can become paired or associated with the trauma experience in the same way that the bell is paired with food.

Following that pairing, the formerly neutral stimuli can become conditioned stimuli that activate the trauma response and symptoms, in other words, traumatic cues.

A traumatic cue can be absolutely anything: an object, a smell, a color, a place, a person, or even a style of interaction. Cues are very idiosyncratic and specific to a person and the context of the trauma.