The Adaptive Stress Response Copy

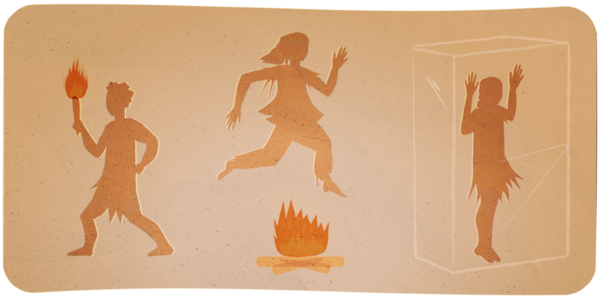

Throughout evolution, humans have been exposed to various stressors from the environment. Over time, the body developed ‘life-saving’ mechanisms to deal with dangerous situations. This is called the ‘fight-or-flight-or-freeze’ response.

When there is no danger and a human is stress-free, the prefrontal cortex—the problem-solving center—is in control, and helps us regulate our thoughts, emotions, body reactions, and behaviors according to our personal goals.

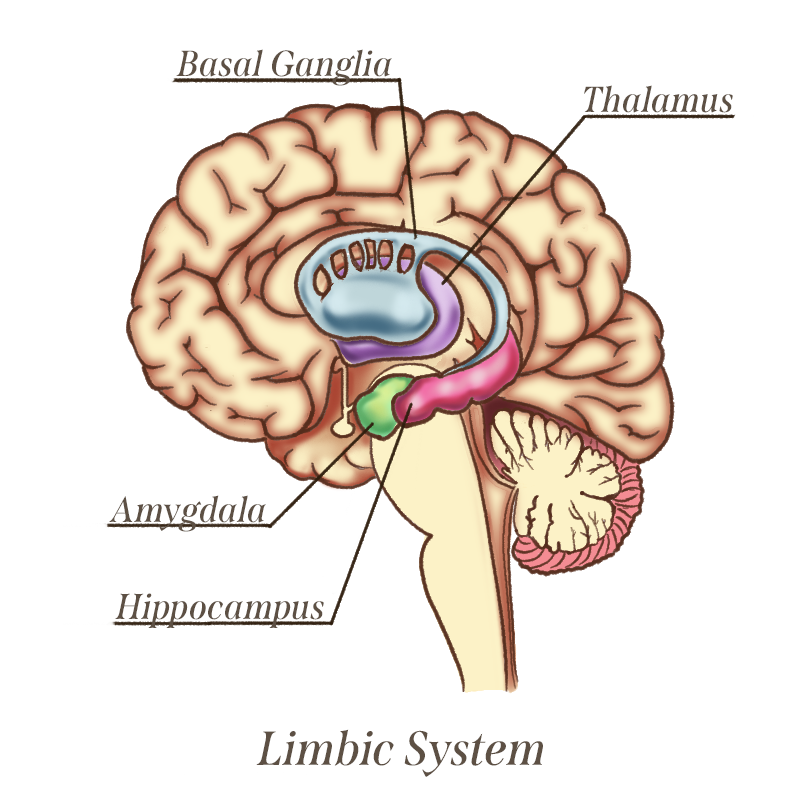

But exposure to severe stressors will trigger the sympathetic nervous system. This causes the adrenal glands to produce more stress hormones and the primitive and emotional brain known as the limbic system (e.g., amygdala, hippocampus) takes control.

The heart rate increases, lungs expand to take in more oxygen, and the blood vessels contract so that more blood goes to the heart.

During this response to this overwhelming situation, we barely have time to think and our minds might even “check out.” This is all a natural and automatic survival response, preparing our bodies to fight, flee, or freeze to manage the threat.

Over-Exposure to Stress

What happens when we are over-exposed to stress? Or repeatedly reminded of a danger that we already went through?

These circumstances produce chronic stress. Chronic stress over-sensitizes our stress alarm button, the amygdala, due to overuse. Just like a sticky key on a computer keyboard that keeps typing even when our fingers are far away, the amygdala keeps activating the emotional part of the brain.

The hippocampus—responsible for memory storage—also plays its part in trauma symptoms. Like a broken record, it gets caught in the moment of trauma: repeating the images, thoughts, and traumatic memories.

This pattern of activation lands us in a constant ‘fight-or-flight-or-freeze’ mode. The ‘fight-or-flight-or-freeze’ response can also be affected by traumatic cues. These are neutral stimuli that become paired with the traumatic event, and going forward, can trigger conditioned reactions in the absence of the original traumatic threat.

This often manifests as ‘trauma symptoms’ or what is referred to as ‘posttraumatic stress symptoms.’

To gain a deeper understanding of the neurobiology of trauma, you may want to explore these additional publications.