Chapter 3. The Trauma Narrative(s) Copy

“Brian, you did so great on the timeline—now it’s time to shift our focus to some of those negative events. Think about the negative experiences from your timeline. I’d like you to choose one or more that you want to talk about and tell it to me out loud, like a story, and I’ll write it down.”

Brian nervously cracks the knuckles on his left hand. “Are you going to show it to anyone?”

You smile reassuringly. “I won’t show it to anybody—it’s just for us as we work together. So once you finish we will make sure everything’s accurate, and later I might ask you some questions to clarify.”

“OK, I’ll try,” he shrugs.

“Try to be as detailed as possible. Imagine it as if it’s happening right now—talk about the story in the present tense. For example, if I were to tell you a story about what I did this morning in the present tense it would be: ‘I’m waking up and taking a shower. Then I’m making toast and coffee for breakfast, then I’m brushing my teeth.’”

Brian scratches his scalp and grumbles, “But why is it necessary to talk about my bad experiences? Can’t I just forget all of that?”

You look Brian in the eyes and reassure him, “It is normal that you want to avoid thinking about them. But, remember when we talked about avoidance?”

“Oh yeah.” He exaggeratedly hits the sides of his head with both hands. “That makes the trauma worse. But I think about them all the time already, and I don’t want to!”

“Trauma memories get encoded in the primitive part of our brain, the emotional part.” You put your paper and pencil down and fold your hands in your lap. You continue, deliberately, “That’s why you keep experiencing those memories over and over again, which causes your symptoms. By talking about it, we process it differently—we transfer it from the primitive to the more sophisticated part of our brain, the part that helps with controlling feelings and problem solving. This way you can file these memories away.”

“As you are telling the story I want you to focus on any feelings or thoughts that come up. Remember we talked about a ‘cue’ being a reminder that causes you to feel, think, and act in the same way that you did during the traumatic experiences—we are looking for clues about those cues also.”

Brian exhales audibly through his nose. “This is going to be hard.”

You smile sadly. “I know. This is distressing. We can always pause and use one of the coping strategies if your stress is ‘climbing up’. Whenever you are ready, we can start. Maybe you can tell me how you’re feeling now using our feelings thermometer?”

“I’m at like a 4 or 5.” He cracks one knuckle on his right hand. “I feel a little nervous, but it’s ok to go ahead.”

“Okay, Brian.” You pause to pick up your pencil and notepad. “And remember that we can pause and use one of your coping tools if the thermometer goes up.”

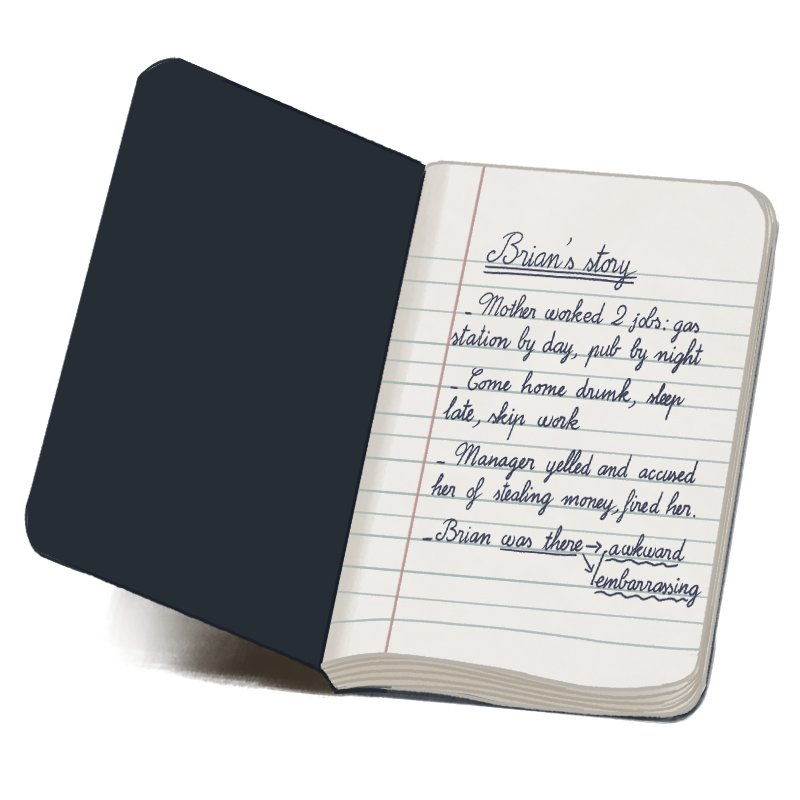

He takes a big breath in. “Ok. Um, I grew up with my mom in the country. It was small…almost everyone was unemployed. Some people worked on farms, but my mom… she worked at a gas station during the day and at a pub in the evening. She always came home from work drunk. She’d drink until late, and then sleep late and skip work.”

You write yourself a note to follow up on later. It reads: What was it like seeing your mom drink? What would you do if she wouldn’t get up? Or feel or think?

Brian continues, “Once we went to the gas station where she worked on her day off—we were supposed to go to the city together. The manager yelled at her, said she stole some money, and he fired her. I was there. He was yelling at her and calling her names. He said she would never find another job because he would tell everyone that she was a thief, a drunk thief…“

“Brian,” you interject, “try to tell your story as if it’s happening right now, as if you are at the gas station. How do you feel?”

“I dunno. Embarrassed. Awkward. It is so embarrassing. There are other people at the gas station and they’re staring at us. My mom loses her temper easily, so she’s yelling loudly and calls him names. Then, at home, she yells at me, because I spilled cheerios on the floor. She beats me up…”

You write yourself another note. It reads: What do you mean by awkward? How did you feel when mom was yelling and beating you? What did you think and do? How do you react now if you hear someone yelling or name calling?

Brian grimaces. “Also, there isn’t much food around. Sometimes I steal food. My mom told me to. She says it isn’t nice to steal, but you have to survive. But they see us on surveillance and want to call the police, so my mom is yelling at them. They leave us alone.”

You’re writing quickly but quietly to record all these details, making sure to add an extra note. This one reads: What do you think about the stealing? Do you still feel like you have to survive?

You gently ask Brian, “How do you feel?”

He closes his eyes. “Scared…I stay home alone a lot. She locks the house so I can’t run away.”

“How do you feel, being home alone?”

“Sometimes it is scary, especially after dark,” Brian’s voice is a hush.

“What do you do?”

His eyes pop open. He stammers, “I…don’t remember. It’s blank in my mind. But someone talked to Social Services. They come to visit us.”

You scrawl another note for follow up: Here’s a gap. What do you do at home alone?

“Brian, how do you feel when they come?”

“Bad. Awkward,” he answers, shaking his head. “But only bad things happen to me anyway. There is one nice lady…she is kind and hugs me. But others are so serious. When I see them, I’m scared they’ll take me away. Every time after they leave, mom is upset and yells. She throws objects and she beats me hard, so I have bruises all over my body.”

During this answer, you’re scribbling to keep up. You write a few notes: Can you tell me what these feelings are? What was scary about it? Do you still worry about this? What kind of objects? How would you feel? What happened after you were beaten?

At his last line you look up and ask Brian, “What do you think?”

He scratches the base of his neck slowly. “That I deserve it. Because I’m no good.”

You suppress a wince. “And what do you do when mom is throwing objects or yelling at you?”

“When I was very small, I didn’t do anything…I’d hide under the table or bed. But now I yell back. And I never hit her, but I do throw objects back. That makes her more upset and she locks herself in her room.”

You make another note: Are there still times that you throw objects?

You’ve filled that sheet with text, so you flip the notebook to a new page as you ask, “How do you feel then?”

Brian hugs his arms around his chest. “Awkward. Lonely. Like no one loves me. Also scared she might hurt herself.”

Another note: What does awkward mean? Do you still believe that no one loves you?

You ask, “And what do you think?”

“I might lose her. I’m responsible if she harms herself.”

You carefully write this question to ask Brian later: Do you still worry you might lose mom?

He continues, “We move to the city. It’s gloomy, but we hear lots of shootings.” He takes a big breath. “Our apartment is small, and always full of people staying over—my mom’s boyfriends, always drunk and people sleeping on the floor. They take drugs together. My mom’s boyfriend offers me some to try once—my mom yells at him and hits him and then he beats her. And he beats me. I run out of the house a lot, but there’s no place to go. I ride my bicycle around, but it isn’t fun.”

You record more questions for later, including: How did you feel about the shootings? And watching your mom and her friends taking drugs? Do you still feel like you have to get away?

You ask Brian if there’s anything else he wants to add to his story.

He rocks forward and back and begins lightly scratching his head with both hands. “My grandma is always angry at me, she keeps telling me things like, ‘You’re just like your mother…you’re a lazy, worthless loser, no good will come from you.’ And my aunt says the same.”

“How do you feel?” you ask gently.

His rocking intensifies for a moment as he blurts, “I feel bad. Like a loser. I am no good.” He pauses and stills. “But I’m also kinda happy when they say I’m like my mom. I want to be like her when she is OK, not drunk, when she is my nice mom. It’s confusing.”

“Brian, how are you feeling now, after telling your story?”

“I dunno,” he shrugs. “Awkward. Sad, I guess.”

You write a note to yourself: What feeling is this?

“Where are you on your feelings thermometer?”

He rubs behind his right ear. “Dunno…a 6.”

“Do you want to use a coping tool now?” you offer.

“Yeah, can I play a videogame?”

You give a “go ahead” nod and he pulls his game console out. Brian’s thumbs rapidly tap at the touchscreen, and his face becomes intensely focused. At one point his tongue is even sticking out.

After a few minutes you inquire, “Brian, can we resume our session?”

“Okay,” Brian laughs, “one sec.” He drops the console in his lap and loudly yawns. He stretches his arms over his head and then tucks the console behind him.

“How do you feel now?”

He grins, sheepishly. “Around 3, I think.”

“That’s good,” you say encouragingly. “It’s great that video games can bring you down to a 3, but remember to keep practicing the other coping tools at home. They can only work if you have a routine and stick with it.”

“Okay,” Brian says with a nod. He gives a thumbs up.

“Before we end for today, I’ll give you one last thing,” you say as you pull out a paper and hand it to Brian, “a worksheet to complete before our next meeting. This is the first feelings worksheet, and you’ll get the second one the next time we meet.”

Brian inspects the paper carefully. “Okay, what is it?”

You point at the three rows marked on the paper. “This sheet asks you about three feelings that are common for individuals who have experienced trauma: fear or anxiety, sadness, and anger. For each of these feelings,” you continue, “write down what you would do when you have that feeling. For example, ‘When I’m scared, I run and hide,’ or ‘I close my eyes.’ Does that make sense?”

Brian nods slowly.

“And bring it next time and we’ll talk about it.”

Brian suddenly looks up at you, worried. “What if I forget?”

“If you forget to write it down, we can do it together in session. But try to think about it and maybe set a reminder on your phone.”

“That’s a good idea,” Brian says as he pulls out his phone.

You wait a couple seconds to give him a start on creating his reminder. “Thanks, Brian. I’ll see you next week!” You rise from your seat, and Brian does the same.

“Thank you!” Brian exclaims. “Have a nice day.”

Brian walks out the door, eyes still glued to his phone.